Two caveats:

First: the photos of the distillation process are by an excellent Lima-based photographer, Luís Montero. He has kindly allowed me to use these photos, and I highly recommend you visit his photo gallery on Pbase which has a superb collection of images from his many trips around his beloved Peru.

Second: I am by no means an authority on pisco; simply, I've researched the subject and culled together information from different resources for both your and my benefit.

Most experts agree the origins of the production of pisco date to the early colonial period in Peru. Since Peru was conquered by Spanish, it is no surprise one of the first crops they planted in the New World were grape vines brought from the Mediterranean region, via the Canary Islands.

Within a few short years there were so many vineyards in the Peruvian colony, in particular in the south of Peru, wine was being exported to other Spanish colonies as well as to the metropolis. Grapes were selected for their quality in order to produce a wine that today would be called 'export quality', while those that did not measure up were discarded or given to the workers to do with as they pleased.

With those cast-off grapes, people began to distill a clear, brandy-like liquor using techniques similar to those employed in the making of chicha, the Andean fermented corn drink. However, this byproduct of the wine production was considered a lesser beverage by the Spanish.

This new beverage did not have a name, although it is reported the Spanish called it aguardiente, or fire water, and soon it became very popular among the indigenous and less-than-wealthy residents of Viceregal Peru.

According to various sources, the oldest written historical record of this grape brandy production in Peru dates to 1613, in the will of a resident of Ica named Pedro Manuel the Greek. In his will, he itemizes his worldly goods, including 30 containers of grape brandy, one barrel of the same spirit, a large copper pot, and all of the utensils needed to produce pisco.

This beverage became popular among sailors that transported products between the colonies and Spain, who praised its strong flavor and even stronger effect. They began calling it pisco, naming it after the port where it could be bought, the city of Pisco (a little over 200 kilometers to the south of Lima). As trade from Peru grew, so did the popularity of pisco until it almost equaled wine in quantity as an export.

In 1641, wine imports from Peru into Spain were banned, severely damaging the wine industry in the colony; only a few vineyards that had parallel wine and pisco operations survived this change. Those that did began to concentrate on pisco production, nearly eliminating wine production in Peru.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, pisco was a mainstay on vessels plying the Pacific. The main reasons for its popularity was its low price and easy availability. This popularity was maintained by pisco until the onset of rum, which was sold at lower prices and had a sweeter flavor.

Pisco was popular in San Francisco and nearby areas of California during the Gold Rush in the 19th century, where it was introduced by Peruvian miners. The famous pisco punch was very popular in this era.

I always thought pisco was just produced along the coastal valleys south of Lima, like Chincha and Ica, but the region around Arequipa is also famed for its vineyards. In fact by 1555, the Vítor valley near Arequipa had some of the first vineyards in Peru and became an important part of the emerging pisco industry.

From what I have read, the current challenge for Peru in terms of its pisco production and exportation is the fact that so much pisco is still made using labor-intensive traditional, artisanal methods not geared for mass production. I see pisco in Peru undergoing something akin to what happened with tequila in Mexico. For many years, the image of tequila was that of a very harsh, strong-tasting drink made to deliver a punch. Something similar could be said about the image of pisco in Peru until the recent past. Now, just like there are small tequila makers using traditional methods to distill a more refined product, there are also many small pisco distillers producing much finer versions of pisco than ever before.

Perú Vinícola is a blog in Spanish about pisco and Peruvian wines where I learned about the importance of Arequipa in Peru's pisco-producing history.

What is sold as 'pure pisco' is made from Quebranta grapes, a non-aromatic variety of the black grape brought from Spain which is what gives it a very particular and characteristic flavor. Other non-aromatic grapes now used in pisco production are Mollar and Negra Corriente. There is also an 'aromatic pisco' made with aromatic Muscat grapes varieties such as Italia, Moscatel, Torontel, and Albilla. A third type of pisco is called acholado, obtained from the mixture of aromatic and non-aromatic grapes.

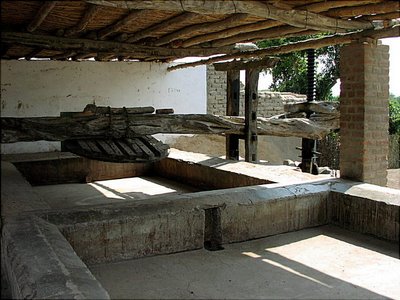

From the vineyards, the grapes are transferred to the lagares, a type of low tub. There they are placed in large piles so wooden presses can squeeze the juice out of them.

Then, this liquid is placed in botijas (also called pisqueras) which are large adobe containers. The containers are placed outdoors where the sun's heat starts the fermentation process, transforming the liquid into an alcoholic beverage. This usually takes two weeks. The favored months for this process are during the Peruvian summer, between February and April.

The liquid is transferred from the botijas into copper containers called falcas or alambiques, known in English as alembics.

The alembics are heated by by fires made with huarango wood, which provides a steady heat and avoid a brusque change of temperature. This has a direct repercussion on the pisco, making it more flavorful.

The distillation process consists in evaporating a liquid and reducing it by contact with cold. Inside the heated alembic, the liquid steams and travels along a serpentine tube which snakes through a vat of cold water. As the steam passes through the part of the tube that is submerged in the cold water, it condenses into small droplets. Those droplets are pisco.

Finally, the pisco comes out of the tube and enters a vat, where it is aged for at least six months.

After the six months are up, the pisco is sampled to ascertain its quality and flavor. I love this picture of an antique sterling silver sommelier pisco cup.

Finally, the pisco is bottled and ready to enjoyed.

Like I said at the onset of this post, I am by no means an expert on pisco production, and I welcome any comments and corrections. I just wanted to share these photos and explain a little of the process of making this traditional Peruvian brandy, used in making Peru's best-known cocktail, the pisco sour.

You may be wondering how the pisco sour came to be, but that is best left for another post.

¡Salud!

Photos: Luís Montero

Peru.Food@gmail.com

.

.

.

Click here for the Peru Food main page.

TAGS: Peru, Peruvian, food, cooking, cuisine, cocina, comida, gastronomía, peruana

TAGS: Peru, Peruvian, food, cooking, cuisine, cocina, comida, gastronomía, peruana

No comments:

Post a Comment