Can a chef be a vehicle for social change? Can the explosion of Peruvian food worldwide transform a nation? For young Peruvians, is their future in Peru or abroad?

Last March, renowned Peruvian chef Gastón Acurio was the featured speaker at the opening of Lima's University of the Pacific 2006-2007 academic year.

His speech in Spanish was published on countless websites and numerous blogs, such as Apuntes de Cocina. Not only did he speak about his own personal philosophy in the creation of his brands, but also how Peruvian cuisine can become a key to fundamentally change Peru.

I've had this speech for a long time in my drafts folder, and I've finally had the time to translate it into English. It doesn't matter that this speech was given over a year ago. As I re-read it, it still has resonance. It is lengthy, but any serious student of Peruvian cuisine will be fascinated to read one man's vision for his craft and ultimately, his country.

Speech given by Gastón Acurio at the opening ceremony for the 2006-07 academic year at the University of the Pacific, March 2006 in Lima.

“While we may believe Peru’s natural resources have been a blessing, history has shown us otherwise.

At one time we had a rubber boom, then it was guano, and now it is minerals. But, when resources run out and the boom times come to an end, we face uncertainty, which can lead to a weakened democracy and give rise to leaders of dubious merits.

Clearly, a country’s growth, stability, and wealth are not due solely to its natural resources.

More important is what a country produces with those resources. For example, Switzerland purchases cocoa and gold to make chocolate, jewelry, and watches. Japan and Korea buy minerals and turn them into automobiles and appliances.

Those countries, in fact all industrialized nations, understand that great wealth is not obtained solely by generic products, but by quality brands which are then exported globally.

From cocoa, Switzerland produces Nestlé; from gold, Rolex. Japan transfoms minerals into Toyota and Nissan; Korea into Samsung. On an individual level, Howard Shultz buys coffee worldwide and brews us Starbucks.

Until recently, Peruvian food was simply a resource. It is beloved by all Peruvians, a source of pride for us, and appreciated by foreigners on trips to Peru.

But, Peruvian cuisine also has great potential to be exported worldwide. However, to do so, the different types of Peruvian cuisines and culinary concepts need to be valued, and then framed conceptually.

There are immense opportunities to take concepts from our local environment and transform them into global brands.

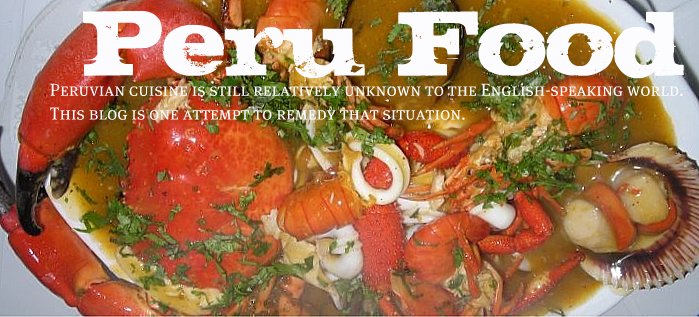

In Peru, we have cocina criolla (traditional coastal cuisine), pollerías (Peruvian-style roast chicken), chifas (Peruvian-Chinese restaurants), cocina novoandina (nouvelle Andean cuisine), Arequipa-style picanterías (traditional eateries in the style of Arequipa), anticucherías (Peruvian-style brochettes), Peruvian sandwiches, Nikkei food (Peruvian-Japanese cuisine), and cebicherías (ceviche and seafood).

If Peru exported these products, they wouldn’t simply be competing against other long-established culinary concepts, such as pizzerias, hamburger stands, sushi bars, and Mexican restaurants. They would also be creating a national brand for Peru, and consequently, providing great economic benefits for the country.

I believe we do understand that this resource so full of potential, our Peruvian cuisine, is ready to expand globally.

So, what’s missing? Why aren’t we taking off as we should?

All the international market research conducted outside Peru indicates that Peruvian is the culinary concept with the greatest growth potential. Internationally, the demand for Peruvian restaurants far surpasses the offer. In fact, right now, investing in a Peruvian restaurant in a city in Europe or North America carries almost zero risk.

In Peru, we have experienced a publishing and educational revolution with regards to our food. In the last ten years, more books have been published about Peruvian cuisine than in Peru’s entire publishing history. In the last five years, 22 officially-recognized cooking schools have opened in Lima, making it the city with more cooking schools than any other in the world.

In 2006, 30% of tourists who came to Peru to visit Cuzco decided to stay in Lima a couple of extra days just because of what they’d read or heard about our food. Journalists are constantly sent here to cover the Peruvian food revolution. Their articles and TV programs all predict an imminent global Peruvian food invasion.

So, if we have all these indicators, why aren’t there Peruvian restaurants in every corner of the world?

I think the answer is quite clear.

We may have the resources. We may have the products. But, we lack the brands.

We lack globally known Peruvian food brands. That’s the key.

Some say we also lack capital or infrastructure. But, almost daily I get offers from Saudi Arabia to Australia from people who want to invest in Peruvian restaurants. We reject most of these offers because I believe everything has its opportune time and place.

What Peruvian chefs and businesspeople have to do is to create a Peruvian brand. And we need to provide investors with not just one concept, but with many different investment options.

To create a brand, you first have to develop it. You have to take a small great idea, a small great dream, and transform it into a powerful philosophy so it grows incrementally until it becomes a model to study, emulate, admire, and ultimately, in which to invest.

With regards to my organization, from the start we began developing culinary concepts that were not just focused on becoming international, but also segmenting into different products. From the onset, we understood restaurants are not just generic places, but spaces that vary for different audiences, for different times, and for different pocketbooks.

Twelve years ago, we opened Astrid y Gastón with $45,000 borrowed from family and friends who had great affection for us but little faith in our vision.

Five years later, after identifying and clarifying our philosophy, and defining ourselves conceptually as Peruvian haute cuisine, placing ourselves at the top of the restaurant price pyramid, we made our first foray abroad, to Chile where Peruvian food already had certain renown.

Then, after receiving awards, we expanded to Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Panama, and Mexico.

Today, each branch of Astrid & Gaston is not only profitable but also a culinary leader in its location. Haute Peruvian cuisine is right there beside haute French, Spanish, and Italian cuisines.

This success prepared the landscape for our other brands to enter the market because there was a guarantee by the prestige of the preceding brand. It’s much easier to win converts by first creating haute cuisine and then sandwiches, than the other way around.

When we opened T’anta, we conceived it as a family restaurant. We define it as a Peruvian bistro or deli, so those who may not be able to afford Astrid y Gastón can also experience the same spirit, but in an informal environment with more affordable prices. We wanted it to have Peruvian flavors, but presented with originality, sophistication, and an artisan spirit.

Opening T’anta was cathartic for us. Astrid & Gaston had always made us feel we were chefs for a small elite in a country of many others. T’anta allows us to show the many others what we want to say with our work and with our brand. Now we have three branches in Lima, and are opening another in 2007. In fact, we’ve finished the process of creating the manuals to make this concept ready for export.

After T’anta, we opened La Mar.

You know, I have many favorite cebicherías, but I always felt they all lacked a philosophy, something to make them competitive leaders in any part of the world.

It saddened me to see such an attractive and sophisticated product as our seafood so undervalued, relegated to quaint holes-in-the wall, where you sat on plastic chairs, and didn’t get good service.

Worse was when an owner decided to improve his or her cebichería, by upgrading the locale or the service, and immediately stopped calling it a cebichería and began calling it simply a ‘seafood restaurant’. There is no awareness that the name cebichería is its greatest virtue, and precisely what differentiates it from any other type of seafood restaurant anywhere in the world

The cebichería, uniquely Peruvian seafood, is what we visualized for the global market.

Once we had the vision, the rest was easy. We knew we had to take advantage of the enormous popularity of ceviche worldwide. And, we knew we had to place the Peruvian cebichería as a concept within the ethnic food segment in order to compete internationally with Japanese sushi bars, with the conviction that one wasn’t better or worse than the other. They were simply different proposals.

The difference would be that in comparison with the almost regal solemnity of a sushi bar, the cebichería has a fun and casual atmosphere. We wanted to maintain the identifying factors of Peruvian cebicherías: the use of cane, wind, and light, but with an improved design. Our vision was to improve and standardize the prime materials, and create a service philosophy in keeping with the happy atmosphere that we wanted to reign. We wanted to conserve the flavors but add imaginative details. We wanted to tell a story: the true story that we Peruvians love ceviche and the cebichería is like our culinary temple.

Now, we are in the process of opening our second La Mar in Lima, and we’ve already sold franchises in Mexico, all of Central America, the Caribbean, and Brazil. In 2007, we hope to enter the market in England and Washington D.C.

For many reasons, we firmly believe the Peruvian cebichería is the Peruvian culinary concept that will expand most quickly worldwide.

And now, our fourth brand.

If you ask ten Peruvians if they like Peruvian-style fried pork sandwiches, pan con chicharrón, all ten will say yes. If you ask them if they like hamburgers, the number decreases to five or six. Nonetheless, when asked how many times that week they ate pan con chicharrón and how many times they ate hamburgers, the latter win out.

We clearly understood the message. The problem was not in our Peruvian-style sandwich; the problem was that there was no brand that had managed to pull ahead of the fast-food chains so that our traditional sandwich shops could meet the desires of our people.

Right now, we’re ready to inaugurate our sandwich shop, Pasquale Hermanos, which will be within the fast-food segment; yet, without renouncing its traditional spirit. Rather, it plans to take advantage of that spirit, and the uniquely Peruvian concept, in order to directly compete with the international fast-food chains.

Pasquale Hermanos will be in the tradition of the great Lima family-run sandwich shops, like those founded by the Carbones, the Cordanos, the Queirolos, and the Palermos. It will be a place where Peruvians can finally feel that going to the Peruvian sandwich shop is no longer an occasional culinary adventure, but a part of daily life; and as such, will force this market segment to reaccommodate itself and open up to a completely Peruvian proposal.

We hope to open many Pasquale Hermanos in Lima. The internationalization of this brand will depend on the success of our cebicherías, our Peruvian bistros, and all the other concepts that will make the brand of Peruvian food sufficiently strong, and thus, expedite the path for Pasquale’s success.

We are currently seeking the location to construct our fifth brand: Panchita.

For centuries, the corner anticucherías, Peruvian brochette stands, were part of the décor and identification of our city, and by default, a tourist attraction.

In recent years, misguided authorities hounded the anticucherías, arguing health concerns instead of providing them tools to upgrade. Nowadays, it is almost impossible to find one of those anticucherías that used to give life and aromas to our street corners.

Paradoxically, at every one of those same street corners there is now a hamburger or fried chicken restaurant with much more dubious health issues than our Doña Panchitas of yesteryear. Additionally, these new additions do nothing to capture the imagination of those who visit us.

In the spirit of regaining this lost tradition, Panchita was born. It pays homage to that culinary tradition and all those anticucherías that once adorned Lima. But, this anticuchería will be recast as a proper restaurant, with good service, a nice design, and a unique philosophy. This anticuchería will be marketed to the world as a Peruvian grill, and will be able to compete internationally with Argentine parrillas and Brazilian rodizios.

Our anticucherías will have clearly defined parameters: they will be festive and the decoration will be evocative of Peruvian haciendas. There will be traditional anticucheras, the grills where anticuchos are cooked, which are different from Argentine parrillas. There will be huancaína and other creamy sauces instead of chimichurri. There will be 25 different types of anticuchos, from the classic beef heart anticucho to the sophisticated tuna anticucho, served with fried yuca, golden-brown fried potatoes, Peruvian corn, and tacu tacu, instead of French fries. There will be Latin music playing instead of tangos. It will be a complete festival of Peruvian flavors instead of just a piece of 500 grams of beef. The street corner anticuchería will be converted into a restaurant and its internationalization will depend on the success of the cebicherías.

We’re currently in the process of creating three additional products.

The first is a chifa, a Peruvian-Chinese restaurant, but one that is a true reflection of a Peruvian-Chinese fusion and not simply a Chinese restaurant with Peruvian touches. Currently, there are five thousand chifas in Peru, but there is not one single brand.

We need to develop the décor, the atmosphere, the music, the service philosophy, and of course, the food ---a food that reflects the true mestizaje, the blending, the fusion--- between the Peruvian and the Chinese which will differentiate it from just Chinese and give it the key to its internationalization.

We are also in the process of creating the pollería, Peruvian roast chicken restaurant, of our dreams. It will be a place where Peruvian side dishes will make it different from other roast chicken restaurants elsewhere. And, where the wood over which the chicken is cooked will give it a unique flavor. Sadly, some businesses today undervalue this concept, and call themselves pollo a la brasa, Peruvian wood-roasted chicken, when in fact, they really use gas. The side dishes and the use of wood will brand it as ‘roast chicken, Peruvian-style’.

We would also like to create a chain of boutique hotels in idyllic places throughout Peru, hotels with a Peruvian Latin spirit, where the design, the price, the service, and the cuisine (already, guaranteed by our previous brands) will be the key to their growth and internationalization.

Finally, we have finished developing what is the beginning of our industrial division.

It is clear that in the future, the growth and expansion of Peruvian cuisine (not only in restaurants abroad but also as a result of international consumer habits) will generate a demand for flavors, sauces, and products which will make it easier to make a ceviche, a tiradito, a causa, and other Peruvian dishes. We’ve already developed the formulas, and now we’re only waiting for the market to be ready to receive them as a brand. We have a strategic manufacturing partner in the Viru Valley, and a passionate distribution partner, both Peruvian, and both ready to commence when the time is right.

You and many others are probably asking yourselves why I have so much faith.

It really isn’t faith. It’s simply a concrete analysis of the situation.

The 1980s saw the great take-off of Mexican cuisine around the world. At that time, there was no Internet, nor were economies globalized, nor were cultural barriers torn down, nor were fusion cuisines in vogue. Yet, at the time, Mexicans went out into the world with their tacos and tequilas, convinced that with them they would conquer the world.

If at the time there might have been 500 Mexican restaurants worldwide, today there must be over 200,000. With that, not only did they manage to introduce their culinary concepts to the world, but they also managed to popularize tequila as well as Corona beer and all the Mexican sauces we see in every supermarket, and of course, Mexican chili, which is so popular that right now in our own Viru Valley we grow jalapeño chilies because Mexican agriculture doesn’t produce enough to meet the global demand.

The same thing happened with the Japanese.

At the beginning of the 1980s, there weren't sushi bars everywhere in the world. Now, there are more than 50,000. Thanks to that, not only did other Japanese products enter the market, but so did other Japanese concepts like teppanyaki, Benihana, and the noodle bars which are currently so fashionable in Europe.

So, if today cultural barriers no longer exist, if the Internet pulls together international culinary concepts, if economies have become irreversibly globalized, if the studies, the international press and the foreign consumer give us constant signals of awaiting us, and if we not only have one but many diverse, sophisticated, and fun culinary products to offer, why should we believe we’re going to fail trying?

Our faith is born out of analysis, not an illusion. Our strength is born out of a sense of duty and the conviction that we chefs are real actors in the process of transformation Peru requires.

We firmly believe that success in Peruvian restaurants worldwide will bring with it many direct and indirect benefits for the country.

If we can imagine a future where, in 20 years time, just like there are now 200,000 Mexican restaurants worldwide there will be 200,000 Peruvian restaurants of all types and in all parts of the world, a future where when we walk along any European street we’ll be able to find an anticuchería next to a pizzeria, a Peruvian sandwich shop next to a hamburger stand, a cebichería alongside a sushi bar, or a criollo restaurant besides a Tex-Mex one, then we can also imagine all the benefits this will bring for our country.

The demand for such simple products such as the yellow potato, ají, red onion, rocoto, or Peruvian limes, will multiply exponentially and with that we’ll finally be able to end one of the worst evils our country faces and that generates so much internal conflict which is then taken advantage of, the poverty of our Andean farmers.

Currently, in Europe’s ethnic markets, a kilo of Peruvian yellow potato sells for five euros. Well, currently the Peruvian farmer gets paid just nine US cents at home for that same kilo. With this new situation, this will change, and with it the permanent bases for the stability of our country.

In this future stage, many industries and products will also have to be developed. There will be sauces, books, magazines, food tourism, culinary assessment, snacks, and dips, all of which will come out of culinary concepts we already have.

Italy, for example, exports products to the tune of 5,000 million dollars solely because a concept called pizza exists worldwide. This is more than an eloquent statement for us to imagine what we could generate around the entire range of Peruvian food concepts. Perhaps, even a much higher figure than that.

Lastly, the fact we have all these concepts and brands worldwide will give the brand of Peru a power of seduction that will not only draw the attention of the international public toward other Peruvian proposals, such as fashion, jewelry, music, industry, and others, but will also motivate and activate the creativity and trust of our youth so they create their own concepts and have the courage to go out into the world with them.

Because of this, we believe Peruvian chefs have many things to do besides simply cook. As members of a generation who have been generously given the opportunity to represent their country, we have a great responsibility with regards to our greatest strength: our cuisine.

That is what the market currently values and appreciates most about us. That is what can generate great change. Not only economic change, but also in the way in which we Peruvians face our personal futures and the future of Peru.

We Peruvians need to seek the wealth amongst ourselves. We have so many opportunities all around us just waiting for someone to value them and to have the strength to convert them into something attractive and powerful to sell to the world.

The key resides in truly understanding we are a great country, with a great and vibrant culture, the result of centuries of mestizaje, our blends and fusions, and which is precisely what makes our cuisine a varied and diverse proposal that has finally captivated the international public.

It is from that mestizaje where we Peruvians need to find our inspiration, not only to create wealth, but also to accept ourselves and love ourselves as a nation. Only then will we be able to find within ourselves all those ideas that will later be transformed into products and brands that will conquer the planet.

Today, I am deeply moved to be able to address you, not just because I can share all these ideas with you, but also to remind you, that like me, you are the most fortunate young people in this country.

You are the ones who had the luck to be born in families that were able to educate you with a love for your country, a country where many children do not even know what love is. It is you who are receiving the best education, like the one I received, like the one my daughters receive, while many other little girls in this country have to work instead of being able to go to school.

This should not only infuriate us as citizens of a country which we love and in which we wish to create wealth and personal success, but it should also convert us into actors to, once and for all, change the situation and finally transform ourselves into a prosperous country, full of wealth and pride, a country in which opportunity is based on equal education for all, and to create a nation that, in conjunction with its citizens, keeps watch and strongly intervenes in the face of arbitrary actions, abuse, and the breaking of the rules agreed to by all.

Believe me, it is only possible to succeed in our personal dreams if first we have a national dream. Personal success will only come if our objectives transcend the personal sphere and form part of a great collective aspiration.

Japan reconstructed a country in ruins to become the power it is today because before they were individuals, her citizens considered themselves Japanese. Germany did the same thing, so did Israel, as well as other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand.

It is that national spirit, a positive national spirit, open to the world, willing to question itself, to tolerate itself, to embrace itself, to seek its integration, to cheer success, and not the nationalism that laments, condemns, divides, closes itself in, and protects mediocrity, which will finally allow Peruvians to attain the definitive essence of our nation and with it, finally, our long-desired prosperity.

In conclusion, I would like to say to you, well really to implore you, to not leave Peru. You are its most fortunate children, our most well-prepared. And if you leave to go abroad to attain a Master’s Degree, make sure you come back.

Don’t leave Peru. This is where opportunity is, this is where wealth is, this is where life has meaning.

Don’t leave because our people need you. Peru needs you. History needs you.

Thank you very much."

Peru.Food@gmail.com

.

.

.